Based in the Tuscany town of Arezzo in Italy, collector and curator Giuseppe Simone Modeo carries multiple hats in the Italian art scene. As Director of public museum Galleria Andrea Sansovino in Monte San Savino, Italy, he also teaches Art Management and Exhibition Design at the Sanremo Academy of Fine Arts in Milan. In addition, he writes about contemporary art for various Italian publications and has written monograph on the art market. His art collection is dedicated to women artists, such as Mona Hatoum, Sophie Calle, ORLAN, and Pipilotti Rist, to name a few.

LARRY’S LIST spoke with the next-generation collector about why he collects exclusively works by women artists, why female voices have been historically marginalized in art, why it is important for him to meet the artists behind the works, as well as the future role of women he foresees in contemporary art.

What was your first encounter with the world of contemporary art?

I come from a youthful love for classical “beauty”: archaeological museums, architecture, monuments that mark our cities as traces of an ancient, layered civilization. At first, I thought that was the full extent of my aesthetic horizon, but just before graduating in economics, some friends who were already visiting galleries and art fairs invited me to join them. That experience was almost enlightening. I realized that contemporary art is not an offense to beauty; it is an expansion of it, into territories where form and meaning intertwine and are expressed through the language of our times.

That moment was a revelation: beauty does not only live in harmony but it can also be urgency, provocation, friction, or a political and intimate vision all at once. From that point on, I felt that observing was not enough; I needed to learn this language and welcome some of these works into my life.

What pushed you to start collecting? Was there a key moment or artwork?

Collecting began from a desire for proximity. Visiting galleries and major art fairs: Artefiera Bologna, Artissima in Turin, and international events like Art Basel and Art Basel Paris offered me a gradual “literacy.” I watched how the light and emotional temperature of an artwork changes depending on context, how it breathes alongside other works, and how it continues to question you over time.

Eventually, I realized I wanted to live with that experience, not just encounter artworks but make space for them in my home, in my daily life.

There was not a single “threshold” piece—it was the sum of many encounters and conversations that transformed curiosity into a sense of urgency. The impulse became clear: to bring home works with which I could establish a participatory, evolving relationship.

What is the primary motivation behind your collection? What does collecting mean to you?

Collecting, for me, is not about accumulating or speculating. It is about building relationships.

An artwork enters my home when I feel it can accompany me over time, challenge my perceptual habits, and refine the way I listen and interpret the world.

Living daily with artworks—like with significant people—produces a kind of knowledge that no other experience can offer. Some mornings, a work feels distant; by evening, it offers comfort. Sometimes it contradicts or admonishes you.

Collecting is an act of responsibility: supporting artistic research, enabling the movement of artworks (through loans and exhibitions), preserving them without immobilizing them. It is also an act of trust: recognizing an artistic voice and investing time, resources, attention, and care.

When and why did you decide to focus exclusively on collecting works by women artists?

This decision emerged while I was still learning the language of contemporary art. The more I listened to stories and trajectories, the more I became aware of a void: women artists were there, but often relegated to the margins of the canon and art-historical hierarchies.

I chose to dedicate my collection to their work with full conviction. For centuries, women have not been given the institutional, economic, cultural, or social conditions necessary to fully share their production or make their poetic and creative voices heard.

Today, collecting women artists’ works is not only an ethical and reparative act—it’s also a precise aesthetic and cultural choice. Their research is powerful, capable of renewing languages and imaginaries, and offering new, bolder horizons of meaning.

Why do you think female voices have been historically marginalized in art?

The systems that shape the art world—academies, patronage, markets, criticism, museums—have long been structured by male perspectives and networks of power that filtered access and built exclusionary narratives.

This marginalization has nothing to do with the quality of the work, but with the conditions that allowed (or prevented) its visibility.

Women artists were often asked to conform to pre-existing models, limiting their capacity for innovation.

To re-center female voices is to expand the field of art itself: more perspectives, more methods, more vocabularies. It is not just a matter of justice; it is a necessity.

What attracts you to the work of contemporary women artists?

I am struck by their honesty and the ability to merge material and biography, gesture and thought.

There is a simultaneously symbolic and practical tradition of weaving and reassembling: threads, textures, or tables around which communities are built.

I see in many women artists a way of questioning that does not rely on force or rupture, but rather digs deep, connects, navigates, and resolves through new synthetic forms.

It is not “gentle” art; it is art that refuses simplification and challenges preconceptions through relational intelligence, bringing depth to bodies, stories, ecosystems, and to universal knowledge itself.

What is the common thread connecting all the works in your collection?

There is an explicit thread and a hidden one. The explicit one is the decision to collect the most significant women artists—it is my compass.

The hidden one is the intensity of the personal connection each work activates in me—artworks that open discussions and compel me to rethink concepts like care, identity, borders, labor, synthesis, and creativity. I favor works that combine formal strength with deep content and can “speak” to each other—creating constellations of meaning, not isolated cries.

What were the first and most recent artworks you acquired?

The first was, in a way, a strict teacher; it taught me to move beyond the idea of beauty as mere formal harmony. The most recent piece merges material research and social responsibility, as if the proposed forms were invitations to reconsider our place in the world. I do not keep a list, not out of secrecy, but because what interests me is the overall journey that the collection maps, and the trajectories that emerge as it evolves.

How many works do you own? Where do you exhibit your collection? Have you ever shown it publicly?

The collection is a living organism, constantly evolving; the number of works alone says little. The works primarily live with me, at home, because daily cohabitation is part of the relationship.

I have already loaned pieces for exhibitions. I fondly recall the recent loan for the major Carol Rama show in Turin in April 2025. I always respond positively to loan requests. I believe a collection is no longer a private or exclusive asset. It should be accessible to interested audiences and institutions.

How do you choose the works that become part of your collection? What guides your acquisitions?

My choices come from deep listening and immersion during gallery and studio visits, fairs, and dialogue with curators. I consider the coherence of the artist’s journey, the solidity of their language, and the urgency of their research. Financial sustainability is a factor, of course, but never the first.

What matters most is the possibility of establishing a deep and lasting connection with the work; it must be able to weave itself into the emotional and intellectual fabric of my life, while also expanding the collection’s narrative horizon.

How important is it for you to meet the artists behind the works?

Very important. Though not a “requirement,” meeting the artist opens up questions about process, timing, and possible interpretations of the work. Sometimes a conversation changes a decision; other times, it confirms it.

Meeting also shapes my responsibilities as a collector: supporting projects, offering loans, or acquiring future works. It is not about fetishizing the artist, but about continuing to engage with the work even after acquiring it.

What role do you think collecting plays in today’s art world?

I envision a participatory and responsible form of collecting—one that supports artistic research over time, facilitates the circulation of artworks, and engages in dialogue with institutions and communities. A collector is not a taste-maker, but a reliable companion offering resources, time, and networks to help works mature and be seen. When collecting works well, it expands the canon and creates the conditions for practices that might otherwise remain on the margins.

How do you imagine your collection ten years from now? What role do you foresee for women artists in the future of contemporary art?

I imagine it more open and larger with more loans, more collaborative projects with foundations and public institutions, as well as more attention to the social contexts in which the artworks operate.

I hope it continues to be a platform for intergenerational and intercultural female voices, fostering dialogue across diverse practices: painting, installation, textile, performance, new media.

I dream of a system where pointing out that someone is a “woman artist” is no longer necessary because their centrality is fully acknowledged, not by quota but by quality and impact.

Who are your favorite artists in your collection?

Any time I try to make rankings in this field, I think of the opening line of a novel I read as a teenager, High Fidelity by Nick Hornby. He suggested that when it comes to impactful cultural experiences, we shouldn’t aim for a single favorite but at least a top five:

“Here are my top five most memorable heartbreaks of all time, in chronological order…”

So, taking inspiration from Hornby, I will share two fives, though I could go on endlessly:

First five: Marlene Dumas, Cecily Brown, Kiki Smith, Sophie Calle, Mona Hatoum

Second five: Tacita Dean, Pipilotti Rist, Katharina Grosse, Rosemarie Trockel, Annette Messager

And I could go on with many other fives—each deeply meaningful, evocative, and dearly loved.

The Art World

What has been your most memorable or joyful moment in the art world?

There are many. I think of the exhibitions I curated in Milan, Turin, Bergamo, Florence, Arezzo, and Perugia, where artworks sparked conversations and formed temporary communities, such as strangers who stayed to discuss under an installation.

And those moments when a piece “chooses me”. It might happen in a crowded fair or a quiet artist studio. You recognize that shift—you know the work will be part of your life—simple, unrepeatable moments that nourish and motivate.

How do you explain the meaning and beauty of contemporary art to friends or newcomers?

I would say that contemporary art is a training ground for understanding reality. It does not try to please; it demands attention. It iss not decoration; it is a tool for knowledge. It disrupts perceptual habits, poses questions, and teaches complexity.

Beauty is not embellishment; it is a form that holds meaning and pushes it forward, forcing us to take a position. Looking at contemporary art means learning to inhabit our time with more sensitivity and greater awareness.

Which emerging women artists should we watch out for?

I prefer not to make rigid rankings, but to suggest research trajectories. Here are three paths I find meaningful:

A material/performative practice focused on the body and community, attentive to process and relationships; and

An installation-based and environmental approach that explores memory, ecology, and place; and

A pictorial or hybrid language that reimagines identity and personal archives.

If desired, I can suggest specific names aligned with my collection and the territories I explore in Italy and Europe. What matters to me is that these artists already have a recognizable voice and are on a growing path, not just “names of the moment.”

Related: BRAMO

Instagram: @giuseppesimonemodeo, @galleriandreasansovino, @bramoyourartcollection

A selection of artists Giuseppe collects:

Beverly Pepper

Marlene Dumas

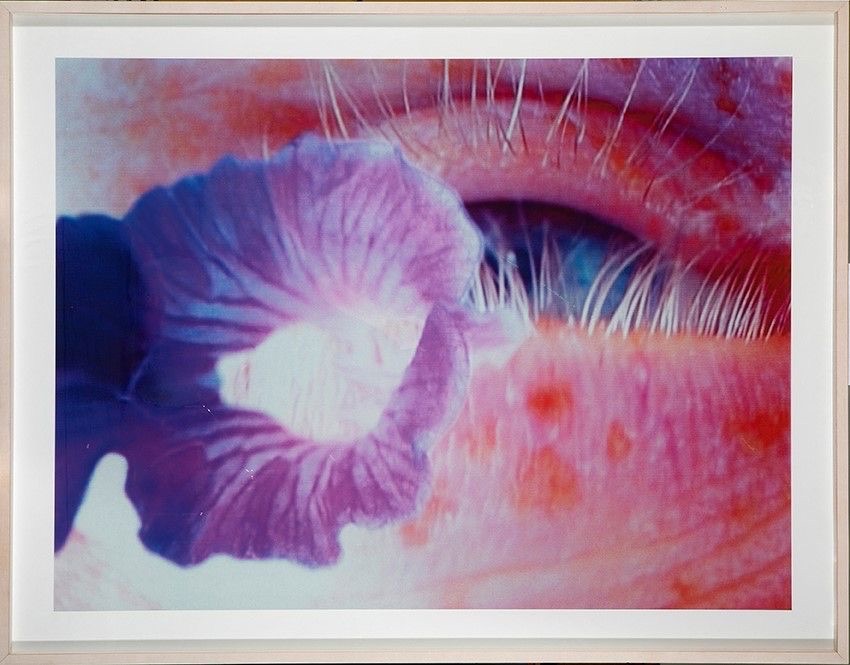

ORLAN

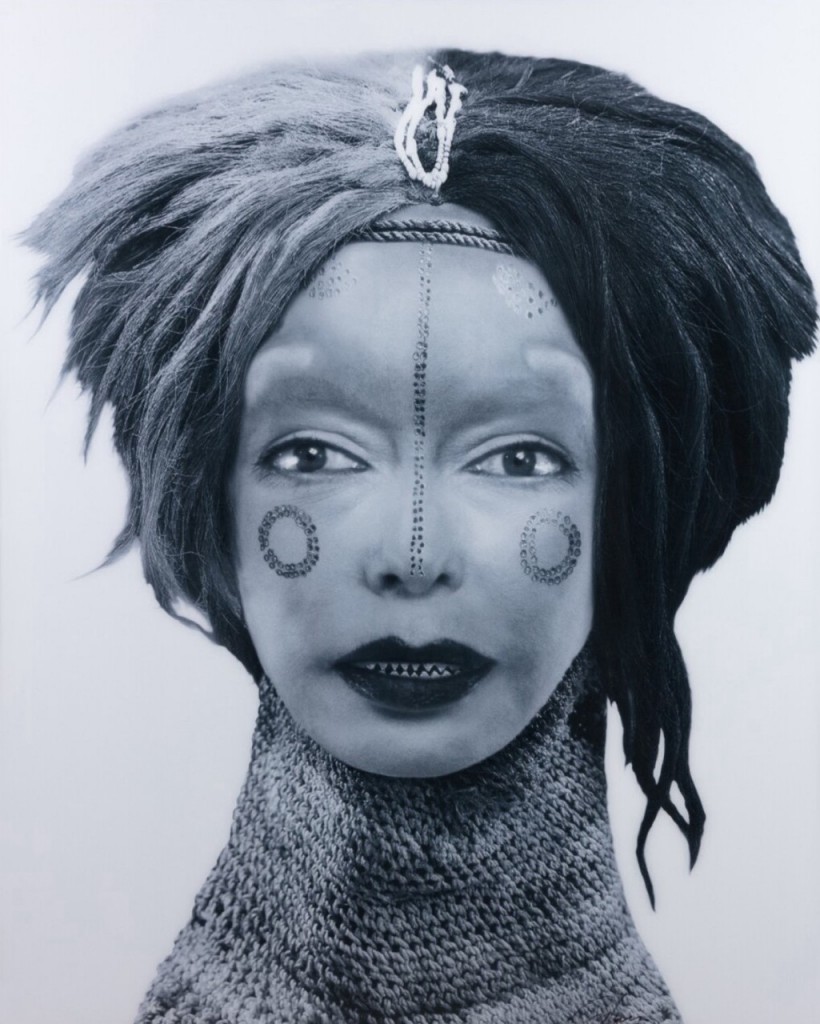

Pipilotti Rist

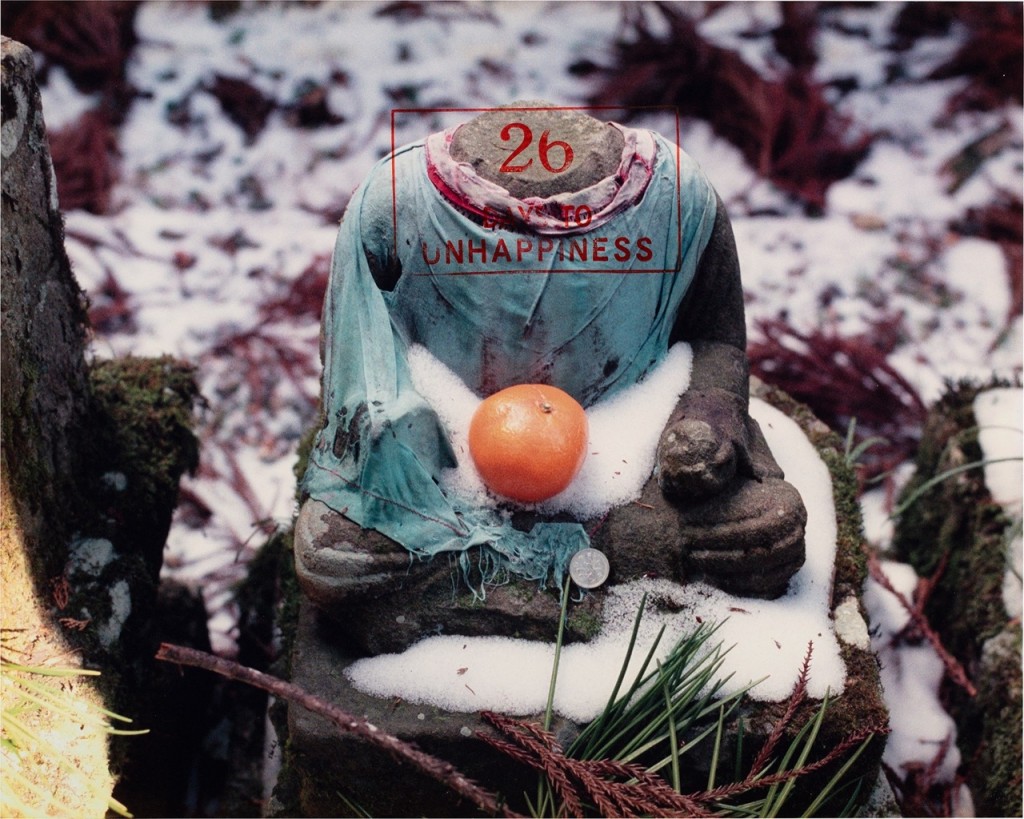

Sophie Calle

By Ricko Leung