Situated in the heart of Malabar Hill, pharma tycoon Swati Jajodia’s home is an oasis in Mumbai’s concrete cityscape. Floating atop an expansive view of the Arabian Sea, Swati’s ever-evolving collection of art and furniture serve as a reflection of her own cultural-historical psyche. She is drawn to items that are born of crucial periods in Indian history, as the nation was re-establishing an independent identity post the British Raj, and also has an eye for contemporary artists and indigenous art. What becomes clear throughout is a sense of vision: to beautify, yes, but more importantly, to educate and empower, to foster discussions and to endlessly inspire. Nothing is off limits, and Swati is anything but your ordinary collector.

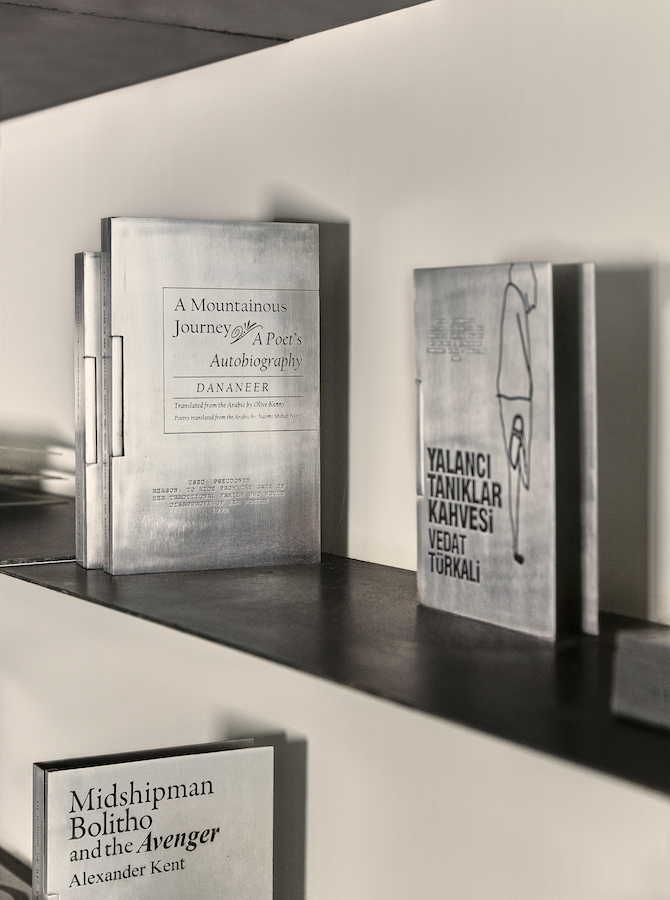

On a sunny Wednesday morning, I’m welcomed into Swati’s home. Light pours in through the massive double-storey windows, bathing each wall in varying colors of the sky. I am greeted by a remarkable Shilpa Gupta installation that resides in the dining room, a wall stacked with metal book casings, nearly magnetizing me in. Gupta brings together 35 world-famous works of literature published by women authors anonymously or under a pseudonym. “I’ve been following her art for nearly 20 years.” Swati explains. Characteristically, Gupta mimics the covers of these books with etched complexity and elegance, inscribing the reason each author chose to publish under a fictitious name. Be it to conceal their gender; to avoid personal or political oppression; to express multiple selves; or to publish a rejected work. Handling metal with the same apparent ease as she does her primary mediums—photo and video, Gupta masterfully plays with an unconventional material. An unexpected juxtaposition that reveals her artistic prowess, she achieves volume through these hollow shapes. The pageless, metal shells perhaps symbolise the absence of the authors’ real identities.

In some ways, Dhiraj Choudhury’s work is traditional. Approaching this canvas, I am instantly reminded of Miró’s “Constellations” series, for their affinities of free-floating forms, intersecting black lines and wandering figures. Understanding the genesis of Choudhurys’ works allows us to fully appreciate his visual language. His art is often misunderstood for ethereal visual manifestations of joy, when in fact, it is a challenge to the viewer’s ability to see what he sees. As a landless refugee, Choudhury had experienced the horror of the Partition of India in 1947 and the Bengal Famine of 1943 firsthand, which went on to form the definitive subjects of his art. What he presents in this piece is almost a rebirth, and he brings that chaos into his imagery—transforming its presence on the canvas to symbolise the freedom he eventually experiences. Choudhury infuses life into his soft geometries— elongated figures emerge from diaphanous layers of emerald and olive. Completed a year before his death, 20 years in the making, the piece is a final theatrical contribution that shows the arc of his full career, and is Swati’s most recent acquisition.

Akin to his hand in bolder mediums, F.N. Souza handles watercolor aggressively. One of Swati’s most treasured pieces, this early work prominently symbolises Souza’s formative years when he was discovering his distinct style. He was in his early twenties at the time, creating small-format watercolors that portrayed the poverty and class disparities in India to which he incessantly bore witness. This 1946 work on paper depicts his now-famous motifs from his early career— scenes from rural life, and the socio-economic condition of the Indians during the British Raj. He paints with great confidence even so early on, his raw and rebellious lines embody the intimate energies that carry over into his paintings produced in his later years. Despite being a politically engaged artist of his time, Souza did not drive an agenda or paint his canvas with an intent to convince. Instead, his work holds a mirror up to the world. Swati’s early Souza captures the critical iconography, and the important shift when artists started to reject the Western academic teaching of the British Raj.

Swati began collecting at 23 with paintings from the Bengal School, a nationalist art movement that celebrated Hindu imagery, and centered around the Government School of Art in Kolkata. “As a close friend of his granddaughter, I would often see Husain paint when we were much younger. In retrospect, that had an immense impact on my artistic inclinations.” She fondly recalls the origins of her appreciation for M.F. Husain. “I was mesmerized by his thick brushstrokes. My father would take me to the Racecourse on Sundays, and that’s where I fell in love with horses. So when I earned enough money, my first artwork had to be his. That is something very special to me.” Husain’s classic horses in neutral tones, alongside a dark, espresso wood, serves as a perfect bridge that seamlessly lets the two living spaces flow into one another. For her family, Swati’s passion for collecting presents an opportunity to live their everyday lives within the context of viewing and engaging; surrounded by fantastic works from Indian history.

What makes Swati’s collection still more surprising is that she is not from an artistic background. Much of her success is down to a strong work ethic and a voracious desire to educate herself about art. Her professional interests— the research of neglected and orphan diseases— are parallel to her search for rare, unconventional pieces of art. This led her to the discovery of not only a mesmerizing Ram Singh Urveti, but also of a unique tribal style of art, Gond Art, a form of folk painting that originated in Madhya Pradesh practiced by the Gond tribe. Urveti learnt to draw and paint on the floor and walls of his home as a child, his art as we see it today celebrates the spirits and rituals of his community. Inspired by Surrealism, he produces fantastical creatures of characteristic patterns in a conflation of the real and the imaginary. Up close, it is easy to get lost in the complexity of the painted surface, the mythical birdlike-animals become metaphors for the artist’s self-made rules.

Swati’s assemblage is original and personal, a diary of events throughout India’s history, ranging from the late 19th century to the present day. Given her diverse intellectual curiosities, each of her works are masterpieces in their own right. Featuring the most exciting Indian avant-garde artists and the Bombay Progressives, the works explore the themes of politics, poverty, hope, and longing. Through her purpose-driven curation, they fit together as part of a compelling and multifaceted story. What she achieves is artistic mastery on the walls, creating a powerful dialogue about makers that found refuge in their artistic practice and shaped the course of Indian Modern Art as we know it. As we circle back to where we began, I ask her, “So what’s next?” Swati plans to collect contemporary international art, namely sculpture and new media. “There’s more to come, more stories to tell,” she says. “I want to fill the walls with art from probably every part of this world.”

Interview by Sunaina Kewalramani

A selection of artists Swati collects:

Dhiraj Choudhury

Julian Opie

Maqbool Fida Husain

Ram Singh Urveti

Shilpa Gupta