William Lim lets a mischievous laugh erupt, and his immaculate poise slips for a second, but then he replies firmly: “No, really, I’m not sad when an artist’s prices rise—it’s a positive thing, a stamp of approval. Though I’m not sure it necessarily does the artist much good. When you become marketable, do you stay true to yourself or do you let the market influence your creativity? Some choose to sway to the market, and that’s where the sadness comes in.”

I’ve come to Lim’s stylish personal studio in the factory district of Wong Chuk Hang on the south of Hong Kong Island. We sit drinking black coffee, looking across at stirring views of Brick Hill, soon to be blocked by the towering developments rising from the new subway station. Behind us, catalogs and objets trouvés inhabit a huge architectural grid of wall-to-ceiling bookshelves, including an arresting variety of chickens, from classic designs on glazed bowls to lifesize fiber-glass replicas by Guangzhou artist Dian Jianyi. Beyond, in dimmer light, is Lim’s display space.

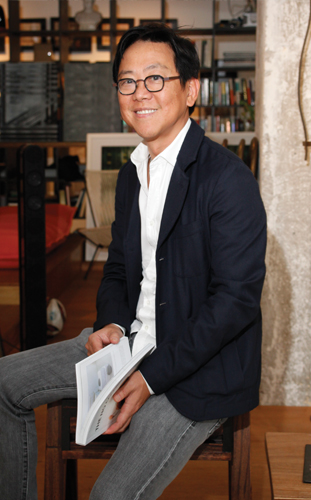

Lim is one of Hong Kong’s leading architects—he has participated twice in Venice’s Architecture Biennale—but he is also among its most important contemporary art collectors. The number of fellow art devotees is now growing, but for a long time his was a lonely pursuit: “My parents didn’t buy art—for the older generation, collecting was not on their agenda, and especially not contemporary art. Hong Kong went through difficult times in the early days, and putting food on the table was the priority. Nowadays, people are getting more receptive to the idea, although there is still a misconception that collecting generates money, that it is about manipulation rather than a genuine interest in art.”

Born in Happy Valley on Hong Kong Island in 1957, Lim started buying young, picking up an impressionistic landscape from a stall in London’s Hyde Park during a holiday in the early 1970s. “There was barely any art scene in Hong Kong at the time, so whenever I traveled I tried to pick something up. I feel art is good at communicating a city’s culture, so I’ve kept the habit.” Studying architecture at New York’s Cornell University, he purchased occasional pieces from the art students sharing his faculty building, but on his return to Hong Kong in 1987 he concentrated on Chinese antiquities.

Lim went on to establish his own practice, CL3 Architecture, in 1992. The firm now has more than 60 employees and offices in Shanghai and Beijing, but there is no sense that Lim is professionally complacent: “You can never relax, but after 20 years we’re at a stage where our clients respect us and let us be creative.” He smiles when I ask if he ever dreamed that he would do so well: “No, not at all, but an architect’s career is never as flamboyant as one might think. And, like many here in Hong Kong, I’m lucky to have ridden the wave of growth in the Chinese market.”

In 2003, to publicize his growing practice, Lim entered the “Lantern Wonderland” competition launched by Hong Kong’s tourist board to boost visitors in the aftermath of SARS. His winning proposal, a monumental dome-shaped bamboo structure incorporating a 360-degree multimedia screen, was unveiled at Victoria Park for the Mid-Autumn Festival to popular and critical acclaim. Lim has since created installations—often utilizing traditional Chinese forms, materials and techniques—at festivals across the globe, and Ladders (2006), first shown at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2006, has recently entered the collection of M+, Hong Kong’s future museum of visual culture. Asked how he balances these artistic pursuits with his professional practice, Lim replies, “I used to struggle: how do you make a choice between being an architect and an artist? Ultimately, I decided that the the best approach was to treat them as two sides of the same coin.”

Lim was lured into the fervid business of collecting Chinese contemporary art during business trips to Shanghai in the early 2000s. His first purchase was cautious—an austere cross painting by local artist Ding Yi. Back in Hong Kong, his quest for a print by Beijing conceptualist Cao Fei in 2006 brought him to Para Site, the city’s leading nonprofit space, then under the vibrant direction of Tobias Berger. Invites to a series of entertainingly chaotic exhibitions followed, and the strength of an emerging generation of Hong Kong conceptual artists became obvious. After a relatively gentle start with Wilson Shieh’s satirical gongbi paintings, Lim’s horizons have expanded to encompass almost all the major figures in contemporary Hong Kong art. His collection now ranges from Kwan Sheung Chi’s dark instructional videos for a suicide attempt to Tsang Kin-Wah’s enormous, beguiling and deceptive vinyl installation for the 2009 Biennale de Lyon.

Lim’s championing of Hong Kong art has led to roles as co-chair at Para Site and advisor to Asia Art Archive and Asia Society Hong Kong. His expertise has also been snapped up by the Tate’s Asia-Pacific Acquisitions Committee, and this year’s Art Basel Hong Kong will see the launch of a substantial book edited by Lim, The No Colors. Based around his collection, it celebrates the new crop of Hong Kong artists, who have risked pursuing unconventional artistic practices despite the uncertainties involved. The aim, according to Lim, “is not just to be a collection catalog but to give an overview of the Hong Kong art scene at a pivotal moment when galleries, collectors and museums are all looking at our artists—Hong Kong is special right now.”

We end our conversation with a walk around his display space, where art handlers are hanging a new work by another local artist, João Vasco Paiva. Yet there is also a strong showing from international artists: a fractured, skeletal mobile by Lee Bul hangs above a cluttered assemblage on castors by Haegue Yang, while a squat, colored-glass-and-metal sculpture by Dennis Oppenheim sits on a neat plywood plinth just behind. “I think it is important to create a visual dialogue between Hong Kong artists and those elsewhere. I’m particularly interested in art produced by Chinese in other parts of the world. Danh Vo was born in Vietnam, but his ancestors come from China, even if he doesn’t consider himself Chinese. And the work he produces has lots of references to immigration and migration, which relate strongly to Hong Kong art.” As if to underscore these intertwinings, when Lim visited Vo’s show dedicated to Chinese-American artist Martin Wong (1946–1999) at the New York Guggenheim last year, he was delighted to find an archival photo of Wong standing in front of one of his recent paintings, which has now found its way to Lim’s studio.

When I hint that one of the rewards of Hong Kong’s art scene must be its rather intimate nature, the giddy laugh returns: “Yes, it’s true, it’s a pretty small community and we all see each other at openings, but it’s growing rapidly. And it’s not competitive—all those involved in art here are very supportive of each other. I just hope it stays that way as artists achieve greater success.” Yet, despite the obvious passion for art that the Hong Kong scene has nurtured, Lim sheepishly admits, “If I had to choose between visiting a good museum show or an interesting building, I would still choose the latter—ultimately architecture is more engrained in me. Last summer I saw Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye outside Paris for the first time—that was an amazing experience.” Lim’s sincere pleasure in these encounters, whether artistic or architectural, is absolute, infectious and really rather endearing.

By John Jervis

This article was originally published in ArtAsiaPacific no.88 May/June 2014 (print content). This article cannot be edited nor shared to third parties without permission from ArtAsiaPacific.